Home » Search results for '' (Page 2)

Search Results for:

Training Service

Videoconference-based training in bilingual videoconferencing

All professionals taking part in videoconferences (VCs) in legal proceedings should receive an induction to VC. Given the increase in legal proceedings requiring the services of an interpreter, such training should also cover bilingual videoconferencing. The training will increase the participants’ understanding of VC as a tool for communication and will help them to evaluate the appropriateness (or otherwise) of using VC in a particular proceeding. Professionals should be trained to develop an understanding of:

- the key concepts relating to VC as a tool for distance communication;

- the rationale for using VC in legal proceedings and the legal provisions that apply to the use of video links;

- the (current) differences between the uses of VC at national and cross-border level;

- the different options for the distribution of VC participants (including an interpreter) in legal proceedings;

- the affordances and limitations of VC communication including bilingual VC communication involving an interpreter;

- the basic principles of (bilingual) communication in a VC and strategies for managing the communication flow in a VC including effective turn-taking and avoidance of overlap;

- the main strategies for managing a (bilingual) VC including management of sound and images, visibility of participants and eye contact.

This training can be conducted face-to-face, or—as we have shown in several training pilots in AVIDICUS3—the medium of VC itself can be used for delivery.

Regardless of how the training is delivered, training sessions should encourage the active participation of those attending through hands-on tasks. Participants should be made to interact with others through the VC equipment in simulations, i.e. with practical activities such as role plays. In order to organise realistic role plays, different groups of stakeholders should be trained together in their respective roles. If possible, technical staff should also attend joint training sessions in order to familiarise themselves with the legal professionals’ and interpreters’ needs while developing confidence in the use of the equipment. Joint training allows potential VC participants to increase awareness of their respective professional needs and will enable them to develop common approaches to the resolution of difficulties and conflicting needs.

Customised support for the planning, design and implementation of solutions for bilingual video-conferencing and practical training for legal professionals and legal interpreters are available through the AVIDICUS 3 project. An outline of this training is available here: AVIDICUS 3 training outline. If you are interested in our training, please contact Prof Sabine Braun at training@videoconference-interpreting.net.

Welcome

This website is devoted to the practice of, and research on, Video-Mediated Interpreting (VMI), i.e. different methods of distance interpreting whereby the participants and/or the interpreter(s) are connected by video link.

VMI is used in connection with both spoken-language and sign-language interpreting and across different fields of interpreting including business, conference and public service or community interpreting (see also What is Video-Mediated Interpreting).

The practice of VMI is not new but has increased and diversified in recent years through technological innovation and evolving demand, but also as a result of cost-cutting in public services. In line with the many forces that drive this development, VMI is often perceived as a double-edged sword. On the one hand, its use as an alternative to onsite interpreting raises questions about interpreting quality and communicative dynamics as well as broader questions concerning the training and skills required of interpreters and their clients in VMI, the interpreters’ working conditions and the clients’ perception of the interpreter. On the other hand, VMI opens up new opportunities for gaining or optimising access to interpreters; meeting linguistic demand; increasing the efficiency of interpreting service provision; and maintaining the sustainability of the interpreting profession.

Research conducted to date has generated mixed results (See also Research on VMI) but the knowledge that we have gained about VMI through research over the past decade has been instrumental in advancing our understanding of its complexities and has begun to inform policies and improve practice. Research will also help to develop viable solutions for VMI.

This website does not advocate the use of VMI. Its aim is to provide a point of reference for work in this field. It documents the results of relevant research, provides links to ongoing and completed projects in this area and makes available publications and resources including project reports, research publications and materials for training. It also provides details about a new training service that uses the medium of videoconference itself to provide training in bilingual videoconference communication.

Most of the resources available at this website were developed in the AVIDICUS projects, i.e. three Euorpean collaborative projects which were carried out from 2008 to 2016 with financial support from the European Commission’s Directorate-General for Justice and focused on VMI in legal proceedings. AVIDICUS stands for Assessment of Video-Mediated Interpreting in the Criminal Justice System.

What is Video-Mediated Interpreting (VMI)?

The evolution of communication technologies has created ample opportunities for distance communication in real time and has led to alternative ways for delivering interpreting services. On the one hand, mobile and internet telephony have made telephone communication more flexible, enabling conference calls with participants in two or more locations. On the other hand, videoconferencing has slowly established itself as a tool for verbal and visual interaction in real time, also between two or more sites.

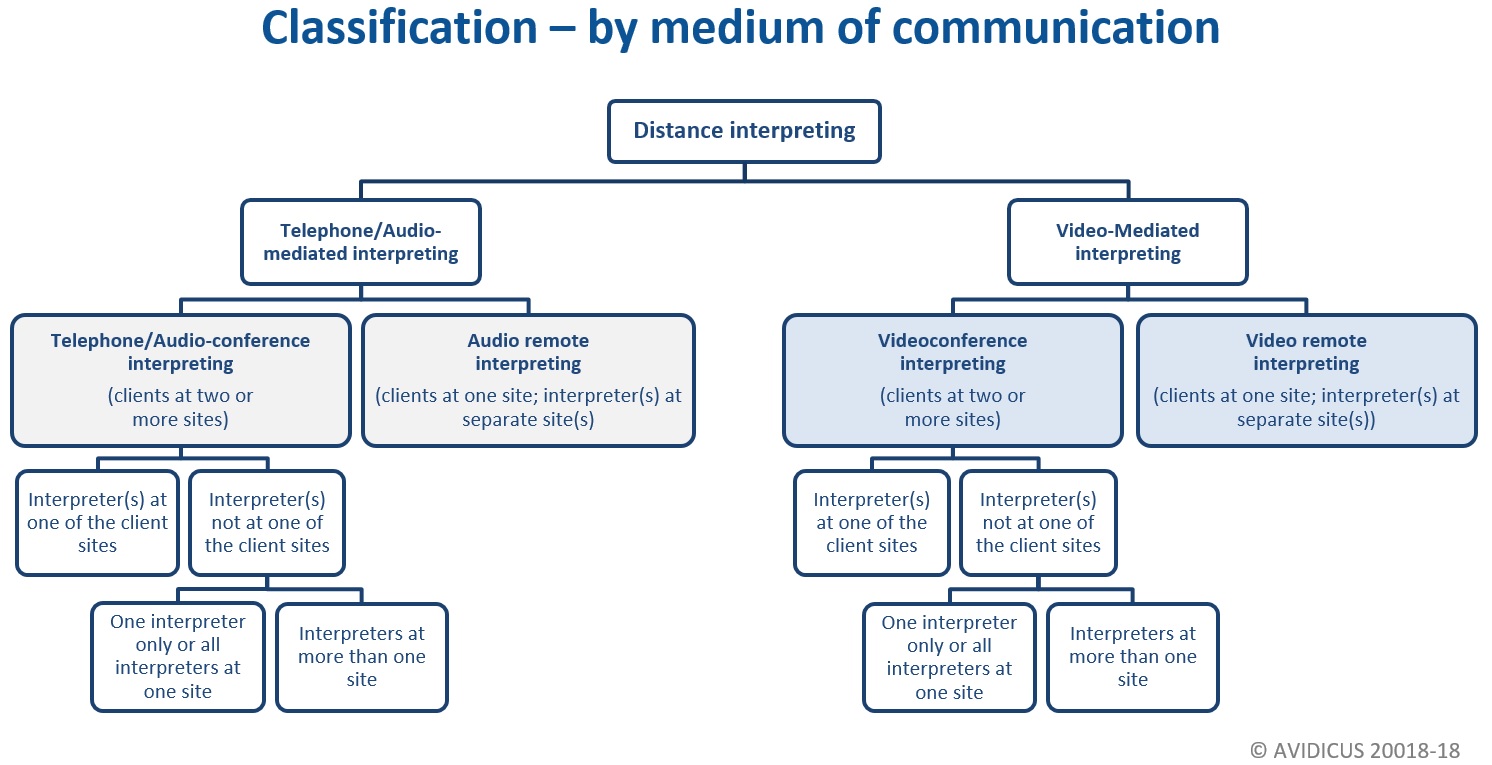

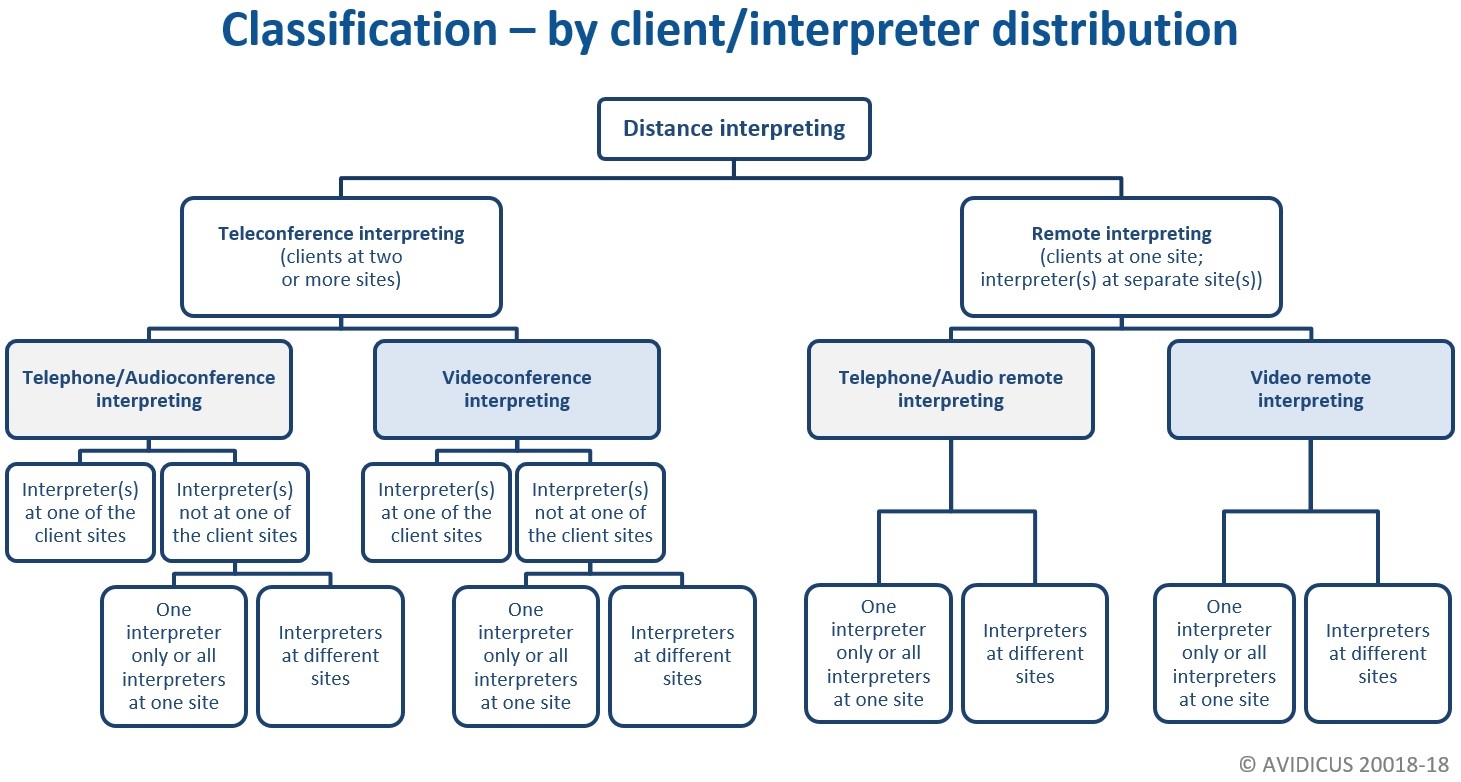

This has also led to different modalities of distance interpreting, i.e. different methods of delivering interpreting services using video links or the telephone. These modalities can be classified in different ways.

Typology of Video-Mediated Interpreting

Based on the medium of communication on which they rely, we can distinguish between Video-Mediated Interpreting (VMI) and Telephone-Mediated Interpreting (see Figure 1). VMI would then be a cover term for Video Remote Interpreting (VRI) or Videoconference Interpreting (VCI).

Video Remote Interpreting (VRI), which refers to the use of video links to gain access to an interpreter in another room, building, town, city or country. In other words, the video link is used to connect the interpreter to the primary participants, who are together at one site. In a further variant of VRI, the primary participants themselves can be distributed across two or more sites, leading to a three-way or multi-point videoconference.

Videoconference Interpreting (VCI), which refers to interpreting in a setting whereby the participants themselves are distributed across two or more sites, and the interpreter is located at one of these sites. In the context of Public Service Interpreting it is sometimes useful to distinguish between two configurations of VIC, i.e. one whereby the interpreter is co-located with the speaker representing the authority and the other whereby the interpreter shares the location of the minority language speaker. This is particularly important in video links used in legal proceedings, e.g. between courts and prisons, where the interpreter can be located in court or in prison.

Many alternative classifications to the one shown above would be possible, e.g. a classification based on the distribution of the main participants and the interpreter(s) (see Figure 2).

Uptake in practice

It should be noted that these methods or modalities have different underlying motivations, i.e. the use of communication technology to link an interpreter with the primary participants vs. its use to link primary participants at different sites, and that they are not interchangeable. However, both methods overlap to a certain extent and share elements of remote working.

The development of VMI has sparked heated debate among practitioners and interpreting scholars and has raised questions of feasibility and working conditions; but the debate has also been linked to the efficiency of service provision and the sustainability of the interpreting profession. (See also the section on Research on VMI).

VMI has been used for simultaneous, consecutive and dialogue interpreting. Whilst uptake in traditional conference interpreting has been relatively slow, there is a growing demand for remote and teleconference interpreting in legal, healthcare, business and educational settings, and both methods are used to deliver spoken and sign-language interpreting alike.

Video-Mediated Interpreting or Bilingual/Multilingual Videoconferencing?

From a client’s point of view, the settings that have been outlined above would be settings of bilingual or multilingual videoconferencing, i.e. virtual meetings, legal proceedings of other events involving all of the following:

- participants who do not share the same language

- one or more interpreters

- a video link

and where the video link is used to connect the participants with each other or with the interpreter(s) or both. The common denominator of these settings is that they involve a combination of videoconferencing with bilingual or multilingual, interpreter-mediated communication. In our Handbook of Bilingual Videoconferencing we have elaborated on this for videoconferencing in legal settings.

A more comprehensive overview of Video-Mediated Interpreting is available in Braun, S. (2015). Remote Interpreting. In Mikkelson, H, & Jourdenais, R (Eds.), Routledge Handbook of Interpreting (pp. 352-367). New York: Routledge.

AVIDICUS 2 (2011-13)

Aims and outcomes

The findings of AVIDICUS 1 suggested that further research was required to investigate how the combination of technological mediation through videoconference technology and linguistic-cultural mediation through an interpreter affects the specific goals of legal communication and to elicit adaptive strategies to mitigate such effects. Moreover, the need to inform EU citizens about how they can benefit from video-mediated interpreting, when appropriately used, has been neglected but can now be met using the European e-Justice portal.

In accordance with this the AVIDICUS 2 project aimed to:

- Disseminate current and emerging knowledge about the uses of video-mediated interpreting (VMI) in criminal proceedings to national authorities, legal practitioners, interpreters and European citizens;

- Improve current insights into these forms of interpreting and identify best practice through research into the behavioural and communicative aspects of VMI in criminal proceedings;

- Improve training opportunities for legal practitioners and interpreters in the use of VMI.

The project produced the following key deliverables:

- A series of European workshops to provide initial training in VMI for approx. 300 legal practitioners and interpreters;

- A set of empirical findings on behavioural/communicative aspects of VMI;

- A set of revised recommendations and guidelines on the uses, benefits and challenges of VMI in criminal proceedings, addressing especially national authorities in all EU member states;

- An advanced module for the joint training of legal practitioners and interpreters in VMI;

- Three ‘mini guides‘ on VMI in criminal proceedings for (a) legal practitioners, (b) interpreters and (c) European citizens, designed to be integrated in the European e-Justice portal;

- A final symposium and publication to disseminate the results of the project.

Please go to the Resources section of this website to see all resources developed in the AVIDICUS projects since 2008.

Partners

AVIDICUS 2 was a co-operative project involving partners in several European countries and external experts with complementary expertise in videoconference technology, videoconference communication, legal interpreting, video-mediated interpreting and academic/professional training.

Co-ordinator:

University of Surrey (GB)

Partners:

Lessius Hogeschool Antwerp (BE)

Institut Télécom (FR)

Ministry of Justice (NL)

Legal Aid Board (NL)

Internal Evaluator:

Ann Corsellis

Resources

This section of the web site gives access to:

Projects

This section provides information on the three AVIDICUS projects, which were carried out from 2008 to 2016 with financial support from the European Commission’s Directorate-General for Justice. AVIDICUS stands for Assessment of Video-Mediated Interpreting in the Criminal Justice System.

AVIDICUS 1 (2008-11)

AVIDICUS 2 (2011-13)

AVIDICUS 3 (2014-16)

Book

Videoconference and Remote Interpreting in Criminal Proceedings

Click here to open/download a pdf version of the table of contents. Click on the titles of the papers below to open/download pdf versions of them.

Sabine Braun and Judith L. Taylor

Introduction 1

Section 1 Framework and context

Caroline Morgan

The new European Directive on the rights to interpretation and translation in criminal proceedings 5

Evert-Jan van der Vlis

Videoconferencing in criminal proceedings 11

Section 2 Video-mediated interpreting in criminal proceedings: from practice to research

Sabine Braun and Judith L. Taylor

Video-mediated interpreting: an overview of current practice and research 27

Sabine Braun and Judith L. Taylor

Video-mediated interpreting in criminal proceedings: two European surveys 59

Sabine Braun and Judith L. Taylor

AVIDICUS comparative studies – part I: Traditional interpreting and remote interpreting in police interviews 85

Katalin Balogh and Erik Hertog

AVIDICUS comparative studies – part II: Traditional, videoconference and remote interpreting in police interviews 101

Joanna Miler-Cassino and Zofia Rybinska

AVIDICUS comparative studies – part III: Traditional interpreting and videoconference interpreting in prosecution interviews 117

Dirk Rombouts

The police interview using videoconferencing with a legal interpreter: a critical view from the perspective of interview techniques 137

Jemina Napier

Here or there? An assessment of video remote signed language interpreter-mediated interaction in court 145

Section 3 Technology

Ronald van den Hoogen and Peter van Rotterdam

True-to-life requirements for using videoconferencing in legal proceedings 187

José Esteban Causo

Conference interpreting with information and communication technologies. Experiences from the European Commission DG Interpretation 199

Annex 1

Annex 2

Annex 3

Annex 4

Section 4 Training

Sabine Braun, Judith L. Taylor, Joanna Miler-Cassino, Zofia Rybinska, Katalin Balogh, Erik Hertog, Yolanda vanden Bosch and Dirk Rombouts

Training in video-mediated interpreting in criminal proceedings: modules for interpreting students, legal interpreters and legal practitioners 205

Annex 1a – Presentation for student interpreters

Annex 1b – Presentation for practising legal interpreters

Annex 1c – Presentation for legal practitioners and police officers

Annex 2 – Student handout

Section 5 Conclusions and implications

Ann Corsellis

AVIDICUS: Conclusions and implications 255

Sabine Braun

Recommendations for the use of video-mediated interpreting in criminal proceedings 265

Bibliography

AIIC (2000) Guidelines for the use of new technologies in conference interpreting. Communicate! March-April 2000. http://www.aiic.net/ViewPage.cfm?page_id=120.

Andres, D. & Falk, S. (2009) Remote and Telephone Interpreting. In D. Andres & S. Pöllabauer (Eds.), Spürst Du wie der Bauch rauf runter?/Is everything all topsy turvy in your tummy? – Fachdolmetschen im Gesundheitsbereich/Health Care Interpreting. München: Martin Meidenbauer, 9-27.

Azarmina, P. & Wallace, P. (2005) Remote interpretation in medical encounters: a systematic review. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare 11, 140-145.

Balogh, K. & Hertog, E. (2012) AVIDICUS comparative studies – part II: Traditional, videoconference and remote interpreting in police interviews. In Braun, S. & J. Taylor (Eds), 119-136. http://www.videoconference-interpreting.net/?page_id=27.

BID (2008) Immigration bail hearings by video link: a monitoring exercise by Bail for Immigration Detainees and the Refugee Council. http://www.refugeecouncil.org.uk/policy/position/2008/bail_hearings.

Böcker, M., & Anderson, B. (1993) Remote conference interpreting using ISDN videotelephony: a requirements analysis and feasibility study. Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society, 37th annual meeting, 235-239.

Braun, S. (2001) ViKiS – Videokonferenz mit integriertem Simultandolmetschen für kleinere und mittlere Unternehmen. In U. Beck (Ed.), 9. Europäischer Kongreß und Fachmesse für Bildungs– und Informationstechnologie (9th European Congress for Educational and Technology Information) (pp. 263-273). Karlsruhe: Schriftenreihe der Karlsruher Kongreß- und Ausstellungs GmbH. https://surrey.academia.edu/SabineBraun/

Braun, S. (2003) Kommunikation unter widrigen Umständen? – Optimierungsstrategien in zweisprachigen Videokonferenz-Gesprächen. In J. Döring, W. Schmitz & O. Schulte (Eds.), Connecting Perspectives. Videokonferenz: Beiträge zu ihrer Erforschung und Anwendung (pp. 167-185). Aachen: Shaker. https://surrey.academia.edu/SabineBraun/

Braun, S. (2004). Kommunikation unter widrigen Umständen? Fallstudien zu einsprachigen und gedolmetschten Videokonferenzen. Tübingen: Narr. https://surrey.academia.edu/SabineBraun/

Braun, S. (2006). Multimedia communication technologies and their impact on interpreting. In M. Carroll, H. Gerzymisch-Arbogast & S. Nauert (Eds), Audiovisual Translation Scenarios. Proceedings of the Marie Curie Euroconferences MuTra: Audiovisual Translation Scenarios Copenhagen, 1-5 May 2006. https://surrey.academia.edu/SabineBraun/

Braun, S. (2007). Interpreting in small-group bilingual videoconferences: challenges and adaptation processes. Interpreting 9 (1), 21-46. https://surrey.academia.edu/SabineBraun/

Braun, S. (2012). Recommendations for the use of video-mediated interpreting in criminal proceedings. In Braun, S. & J. Taylor (Eds), 301-328. https://surrey.academia.edu/SabineBraun/

Braun, S. (2013) Keep your distance? Remote interpreting in legal proceedings: A critical assessment of a growing practice. Interpreting 15 (2), 200-228. https://surrey.academia.edu/SabineBraun/

Braun, S. (2014). Comparing traditional and remote interpreting in police settings: quality and impact factors. In Viezzi, M, & Falbo, C (Eds.), Traduzione e interpretazione per la società e le istituzioni (pp. 161-176). Trieste: Edizioni Università di Trieste. https://surrey.academia.edu/SabineBraun/

Braun, S. (2015). Remote Interpreting. In Mikkelson, H, & Jourdenais, R (Eds.), Routledge Handbook of Interpreting (pp. 352-367). New York: Routledge. https://surrey.academia.edu/SabineBraun/

Braun, S. (2015). Videoconference Interpreting. In Pöchhacker, F, Grbic, N, Mead, P, & Setton, R (Eds.), Routledge Encyclopedia of Interpreting Studies. New York: Routledge. https://surrey.academia.edu/SabineBraun/

Braun, S. (2015). Remote Interpreting. In Pöchhacker, F, Grbic, N, Mead, P, & Setton, R (Eds.), Routledge Encyclopedia of Interpreting Studies. New York: Routledge. https://surrey.academia.edu/SabineBraun/

Braun, S. (2016). What a micro-analytical investigation of additions and expansions in remote interpreting can tell us about interpreter’s participation in a shared virtual space. Journal of Pragmatics. Special Issue “Participation in Interpreter-Mediated Interaction”.

Braun, S. (2016). Videoconferencing as a tool for bilingual mediation. In B. Townsley (Ed.), Understanding Justice: An enquiry into interpreting in civil justice and mediation. London: Middlesex University.

Braun, S. (2016). The European AVIDICUS projects: Collaborating to assess the viability of video-mediated interpreting in legal proceedings. European Journal of Applied Linguistics, 1-7.

Braun, S. & Balogh, K. (2016). Bilingual videoconferencing in legal proceedings: Findings from the AVIDICUS projects. Proceedings of the Conference on Electronic protocol – an opportunity for a transparent and fast process, Warsaw May 2015. Warsaw: Ministry of Justice of Poland, 21-34.

Braun, S., Kohn, K. (2001) Dolmetschen in der Videokonferenz. Kommunikative Kompentenz und Monitoringstrategien. In H. Gerzymisch-Arbogast (Ed.), Kultur und Übersetzung: Methodologische Probleme des Kulturtransfers – mit Ausgewählten Beiträgen des Saarbrücker Symposiums 1999 (Jahrbuch Übersetzen und Dolmetschen 2/2001) (pp. 3-32). Tübingen: Narr. https://surrey.academia.edu/SabineBraun/

Braun, S., Kohn, K., Mikasa, H. (1999) Kommunikation in der mehrsprachigen Videokonferenz: Implikationen für das Dolmetschen. In H. Gerzymisch-Arbogast, D. Gile, J. House & A. Rothkegel (Eds.), Neuere Fragestellungen der Übersetzungs- und Dolmetschforschung (pp. 267-305). Tübingen: Narr. https://surrey.academia.edu/SabineBraun/

Braun, S., Sandrelli, A. & Townsley, B. (2014). Technological support for testing. In C. Giambruno (Ed.), Assessing legal interpreter quality through testing and certification: the QUALITAS project (pp. 109-139). Alicante: Publicaciones de Alicante.Braun S. (2013) ‘Keep your distance? Remote interpreting in legal proceedings: A critical assessment of a growing practice’. Interpreting 15 (2), 200-228. https://surrey.academia.edu/SabineBraun/

Braun, S. & J. Taylor (Eds.) (2012a). Videoconference and remote interpreting in criminal proceedings. Antwerp: Intersentia. https://surrey.academia.edu/SabineBraun/

Braun, S. & Taylor, J. (2012b). Video-mediated interpreting: an overview of current practice and research. In Braun, S & J Taylor (Eds), 33-68. https://surrey.academia.edu/SabineBraun/

Braun, S. & Taylor, J. (2012c).Video-mediated interpreting in criminal proceedings: two European surveys. In Braun, S & J Taylor (Eds), 69-98. https://surrey.academia.edu/SabineBraun/

Braun, S. & Taylor, J. (2012d). AVIDICUS comparative studies – part I: Traditional interpreting and remote interpreting in police interviews. In Braun, S & J Taylor (Eds), 99-118. https://surrey.academia.edu/SabineBraun/.

Braun, S., Taylor, J., Miler-Cassino, J., Rybinska, Z., Balogh, K., Hertog, E., Vanden Bosch, Y., Rombouts, D. (2012).Training in video-mediated interpreting in criminal proceedings: modules for interpreting students, legal interpreters and legal practitioners. In S Braun & J Taylor (Eds), 137-159. https://surrey.academia.edu/SabineBraun/

Buck, V. (2000) An Interview with Panayotis Mouzourakis. Communicate! March-April 2000, http://aiic.net/ViewPage.cfm/page121.htm.

Chen, N. & Ko, L. (2010) An online synchronous test for professional interpreters. Education, Technology & Society 13 (2), 153-165.

Connell, Tim (2006) The application of new technologies to remote interpreting. Linguistica Antverpiensia NS 5, 311-324.

Corsellis, A. (2011) AVIDICUS: Conclusions and implications. In Braun, S. & J. Taylor (Eds), 255-264. http://www.videoconference-interpreting.net/?page_id=27.

Daly, A. (1985) Interpreting for international satellite television. Meta 30 (1), 91-96. http://www.erudit.org/revue/meta/1985/v30/n1/002445ar.pdf.

Ellis, S.R. (2004) Videoconferencing in Refugee hearings. Ellis Report to the Immigration and Refugee Board Audit and Evaluation Committee. http://www.irb-cisr.gc.ca/Eng/transp/ReviewEval/Pages/Video.aspx.

Esteban Causo, J. (2012) Conference interpreting with information and communication technologies. Experiences from the European Commission DG Interpretation. In Braun, S. & J. Taylor (Eds), 227-232. http://www.videoconference-interpreting.net/?page_id=27.

Fagan, M., Diaz, J., Reinert, S. Sciamanna, C. & Fagan, D. (2003) Impact of interpretation method on clinic visit length. Journal of General Internal Medicine 18, 634-638. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/picrender.fcgi?artid=1494905&blobtype=pdf.

Fowler, Y. (2007) Interpreting into the ether: interpreting for prison/court video link hearings. Proceedings of the Critical Link 5 conference, Sydney, 11-15/04/2007. http://www.criticallink.org/files/CL5Fowler.pdf.

Gany, F. et al. (2007) Patient satisfaction with different interpreting methods: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of General Internal Medicine 22 Suppl 2, 312-318. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17957417.

Hlavac, J. (2013) A cross-national overview of translator and interpreter certification procedures. Translation & Interpreting 5 (1), 32-65.

Hornberger, J., Gibson, C., Wood, W., Dequeldre C., Corso, I., Palla, B. & Bloch, D. (1996) Eliminating language barriers for non-English-speaking patients. Medical Care 34 (8), 845-856. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8709665.

Jones, D., Gill, P., Harrison, R., Meakin, R., & Wallace, P. (2003) An exploratory study of language interpretation services provided by videoconferencing. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare 9, 51-56. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12641894.

Kelly, N. (2008) Telephone interpreting: A comprehensive guide to the profession. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

Ko, L. (2006): The need for long-term empirical studies in remote interpreting research. A case study of telephone interpreting. Linguistica Antverpiensia NS5, 325-338.

Kuo, D. & Fagan, M. (1999) Satisfaction with methods of Spanish interpretation in an ambulatory care clinic. Journal of General Internal Medicine 14, 547-550. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/picrender.fcgi?artid=1496734&blobtype=pdf.

Kurz, I. (1997) Getting the message across – simultaneous interpreting for the media. In M. Snell-Hornby, Z. Jettmarová & K. Kaindl (Eds), Translation as intercultural communication. Amsterdam: Benjamins, 195-206.

Kurz, I. (2000) Mediendolmetschen und Videokonferenzen. In Kalina, Buhl & Gerzymisch-Arbogast (Eds), Dolmetschen: Theorie – Praxis – Didaktik; mit ausgewählten Beiträgen der Saarbrücker Symposien. St. Ingbert: Röhrig Universitätsverlag, 89-106.

Kurz, I. (2000): Tagungsort Genf/Nairobi/Wien: Zu einigen Aspekten des Teledolmetschens. In M. Kadric, K. Kaindl & F. Pöchhacker (Eds.), Festschrift für Mary Snell-Hornby zum 60. Geburtstag. Tübingen: Stauffenburg, 291-302.

Lee, J. ( 2007) Telephone interpreting — seen from the interpreters ’ perspective. Interpreting, 2 (2), pp.231–252.

Lee, L., Batal, H., Maselli, H. & Kutner, J. (2002) Effect of Spanish interpretation method on patient satisfaction in an urban walk-in clinic. Journal of General Internal Medicine 17 (8), 641-645. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1495083/.

Locatis, C., Williamson, D., Gould-Kabler, C., Zone-Smith, L., Detzler, I., Roberson, J., Maisiak, R. & Ackerman, M. (2010) Comparing in-person, video, and telephonic medical interpretation. Journal of General Internal Medicine 25 (4), 345–350. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2842540/

Locatis, C., Williamson, D., Sterrett, J., Detzler, I. & Ackerman, M. (2011) Video medical onterpretation over 3G cellular networks: A feasibility study Telemedicine and e-Health 17 (10), 809-813.

Luccarelli, L. (2011) Remote interpreting rides again. http://aiic.net/page/3710/remote-interpreting-rides-again/lang/1 (accessed 24/01/2014)

Masland, M., Lou, C., Snowdon, L. (2010) Use of Communication Technologies to Cost-Effectively Increase the Availability of Interpretation Services in Healthcare Settings. Telemedicine and e-Health 16:6, 739-745.

Miler-Cassino, J. & Rybinska, Z. (2011) AVIDICUS comparative studies – part III: Traditional interpreting and videoconference interpreting in prosecution interviews. In Braun, S. & J. Taylor (Eds), 117-136. http://www.videoconference-interpreting.net/?page_id=27.

Moser-Mercer, B. (2003) Remote interpreting: assessment of human factors and performance parameters. Communicate! Summer 2003. http://aiic.net/ViewPage.cfm?page_id=1125.

Moser-Mercer, B. (2005) Remote interpreting: issues of multi-sensory integration in a multilingual task. Meta 50 (2), 727-738. http://www.erudit.org/revue/meta/2005/v50/n2/011014ar.pdf.

Mouzourakis, P. (1996) Videoconferencing: techniques and challenges. Interpreting 1 (1), 21-38.

Mouzourakis, P. (2003) That feeling of being there: vision and presence in remote interpreting. Communicate! Summer 2003. http://www.aiic.net/ViewPage.cfm/article911.htm.

Mouzourakis, P. (2006) Remote interpreting: a technical perspective on recent experiments. Interpreting 8 (1), 45-66.

Napier, J. (2011) Here or there? An assessment of video remote signed language interpreter-mediated interaction in court. In Braun, S. & J. Taylor (Eds), 145-184. http://www.videoconference-interpreting.net/?page_id=27.

Napier, J. (2012) Here or there? An assessment of video remote signed language interpreter-mediated interaction in court. In S. Braun & J. Taylor (Eds.), 167-214.

Niska, H. (1999) Quality Issues in Remote Interpreting. In A. Alvarez Lugris & A. Fernandez Ocampo (Eds.), Anovar / Anosar estudios de traduccion e interpretaccion. Vigo: Universidade de Vigo, 109-21.

Niska, H. (2002) Community interpreter training: Past, present, future. G. Garzone & M. Viezzi (Eds.), Interpreting in the 21st Century. Amsterdam: Benjamins, 133–144.

O’Hagan, M. & Ashworth, D. ( 2002) Translation-Mediated Communication in a Digital World. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

O’Hagan, M. (1996) The coming industry of teletranslation. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

Oviatt, S. & Cohen, P. (1992) Spoken language in interpreted telephone dialogues. Computer Speech and Language 6, 277-302.

Ozolins, U. (2011) Telephone interpreting: Understanding practice and identifying research needs. Translation & Interpreting 3 (1), 33-47.

Paneth, E. (1057/2002) An investigation into conference interpreting. In F> Pöchhacker & M. Shlesinger (Eds), The Interpreting Studies reader. London: Routledge, 31-41.

Paras, M., Leyva, O., Berthold, T. & Otake, R. (2002) Videoconferencing medical interpretation. The results of clinical trials. Oakland: Health Access Foundation.

Parton, S. (2005) Distance education brings deaf students, instructors, and interpreters closer together: A review of prevailing practices, projects, and perceptions. International Journal of Instructional Technology and Distance Learning 2 (1), 65-75.

Price EL, Pérez-Stable EJ, Nickleach D, López M, K. L. (2012) Interpreter perspectives of in-person, telephonic, and videoconferencing medical interpretation in clinical encounters. Patient Educ Couns, 87 (2), 226–232.

Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf (2005) Video Relay Service Interpreting.

http://www.rid.org/UserFiles/File/pdfs/Standard_Practice_Papers/Drafts_June_2006/VRS_SPP.pdf.

Rombouts, D. (2012)The police interview using videoconferencing with a legal interpreter: a critical view from the perspective of interview techniques. Braun, S. & J. Taylor (Eds), 159-166. http://www.videoconference-interpreting.net/?page_id=27.

Rosenberg, B. A. (2004) A Quantitative Analysis of Telephone Interpreting. In I. Kemble (Ed), Using Corpora and Databases in Translation. Portsmouth: University of Portsmouth, 156-165.

Rosenberg, B.A. (2007) A data driven analysis of telephone interpreting. In C. Wadensjö, B. Englund Dimitrova & A.L. Nilsson (Eds), The Critical Link 4. Professionalisation of interpreting in the community. Amsterdam: Benjamins, 65-76.

Roziner, I. & Shlesinger, M. (2010), Much ado about something remote: Stress and performance in remote interpreting. Interpreting 12:2, 214–247.

Saint-Louis L., Friedman E., Chiasson E., Quessa A., Novaes F. (2003) Testing new technologies in medical interpreting. Somerville, Massachusetts: Cambridge Health Alliance. http://www.challiance.org/Resource.ashx?sn=CommunityAffairstnthndbk.

Selhi, T. (2000) Interpretation on the Internet. Communicate! October 2000. http://www.aiic.net/ViewPage.cfm/article154.htm.

Swaney, I. (1997) Thoughts on Live vs. Telephone and Video Interpretation. Proteus 6 (2) http://www.najit.org/membersonly/library/Proteus/HTML%20Versions/back_issues/swaney.htm.

Van den Hoogen, R. & Van Rotterdam, P. (2012) True-to-life requirements for using videoconferencing in legal proceedings. In Braun, S. & J. Taylor (Eds), 215-226. http://www.videoconference-interpreting.net/?page_id=27.

Van der Vlis, E. (2012) Videoconferencing in criminal proceedings. In S Braun & J Taylor (Eds), 13-32. http://www.videoconference-interpreting.net/?page_id=27.

Wadensjö, C. (1999) Telephone interpreting and the synchronisation of talk in social interaction. The Translator 5 (2), 247-264.

About

AVIDICUS 1 (2008-11)

Aims and outcomes

The overall aim of the AVIDICUS 1 project was to explore whether the quality of video-mediated interpreting (VMI) is suitable for criminal proceedings, which would constitute a significant step towards improving judicial cooperation across Europe. Furthermore, AVIDICUS 1 aimed to address the training of interpreters and legal practitioners in VMI.

The specific objectives of the project were:-

- To identify situations where different configurations of VMI would be most useful from a criminal proceedings point of view and specify a set of relevant situations;

- To assess the reliability of VMI in these situations from an interpreting point of view through a series of comparative case studies (face-to-face interpreting vs. VMI) and formulate a set of recommendations for EU criminal justice services on the use of VMII in criminal proceedings;

- To develop and implement training modules on VMI based on the findings from (2) in order to improve the knowledge of interpreter students, practising legal interpreters and legal practitioners with regard to these new forms of interpreting.

The project developed an improved understanding of the settings in which VMI is relevant and produced the following key deliverables:

- A set of recommendations for the use of VMI in criminal proceedings (benefits, risks, guidelines for best practice),

- A set of VMI training modules for legal practitioners, practising interpreters and interpreting students,

- A final symposium to disseminate the major findings to relevant target groups (with book publication to follow).

Please go to the Resources section of this website to see all resources developed in the AVIDICUS projects since 2008.

Partners

AVIDICUS 1 was a co-operative project involving partners in several European countries and external experts with complementary expertise in videoconference technology, videoconference communication, legal interpreting, video-mediated interpreting and academic/professional training.

Co-ordinator:

University of Surrey (GB)

Partners:

Lessius Hogeschool Antwerp (BE)

Local Police Antwerp (BE)

Ministry of Justice (NL)

Legal Aid Board (NL)

TEPIS Polish Society of Sworn and Specialised Translators (PL)

Internal Evaluator:

Ann Corsellis

The projects desctibed at this website have been funded with support from the European Commission. This website reflects the views only of the authors, and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein.

The projects desctibed at this website have been funded with support from the European Commission. This website reflects the views only of the authors, and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein.